Conclusion

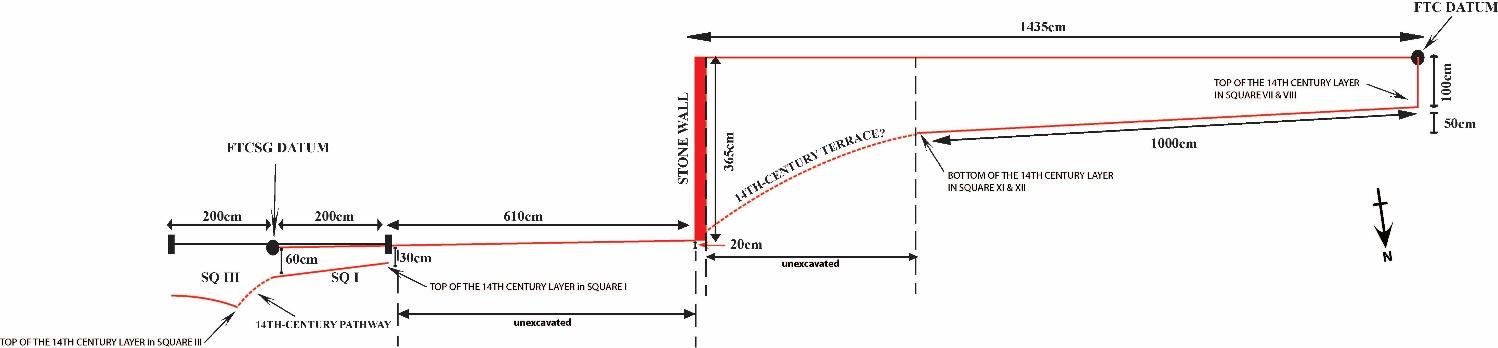

Analysis of the stratigraphy and distribution of artifacts at the FTCSG gives a strong indication that the site marks the location of a footpath which would have been used in the 14th century to access the upper slope and top of the hill. The path would certainly have served as an access way for the site of the hypothesized workshop located at the Fort Canning Archaeological Dig Site, now called Artisan’s Garden, following the 2019 Bicentennial renovation of the site.

This site is unique in 14th-century Singapore in that it does not seem to have been used for a particular activity. It was probably a low-energy area at the side of a footpath used for casual discard of rubbish. No doubt the sherds of broken pottery were brought down the hill from the workshop zone 25 meters uphill, the religious site with brick shrines another 50 meters to the west and higher up the hill, and the palace site that would have been on the summit of the hill. This summit was later flattened by the British to build Fort Canning in 1858. In 1928 the fort buildings were demolished to create the service reservoir, which now occupies about 10 hectares on top of the hill.

The fact that artifacts are denser on the downhill side of the site than the uphill side suggests that they were dumped there so that they would not obstruct the passage of people walking up and down the hill. Some sherds of the same objects were nested within each other, showing that they had been stacked on top of each other when they were dumped. No doubt they were accompanied by other sorts of rubbish of organic materials, which have not survived.

The presence of a few pieces of glass and high-quality ceramics indicates that the people who used the path and dumped the rubbish there were associated with the elite who lived on the hilltop. In other parts of 14th-century Singapore, rubbish seems to have been discarded indiscriminately, but here there seems to have been an intentional effort to keep some parts of the hill clean, another piece of evidence that suggests that the hill was reserved for the elite and those who served them.

Like other parts of Fort Canning Hill which have been excavated, all Temasek-period artifacts date from the 14th century. This contrasts with the situation on the flat land along the Singapore River and the Padang, where evidence of continued occupation in the 15th and 16th centuries is plentiful. The pathway, like the palace, temple zone, and palace workshops, was probably abandoned around 1396 when the palace was attacked by people from Patani, southern Thailand who wished to avenge the murder of Singapore’s previous ruler by a usurper from Sumatra known as Parameswara.

For further information on the archaeology of Fort Canning and the precolonial history of Singapore, see J.N. Miksic, Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea (Singapore: NUS Press, 2013), and other reports in this series.