4. Results

This section presents the data and the provisional interpretation of the finds that were sampled from excavation units EMP 001 to EMP 007 for this report. A total of 160,957 artefacts, weighing 890 kilograms (kg), were processed for this report.

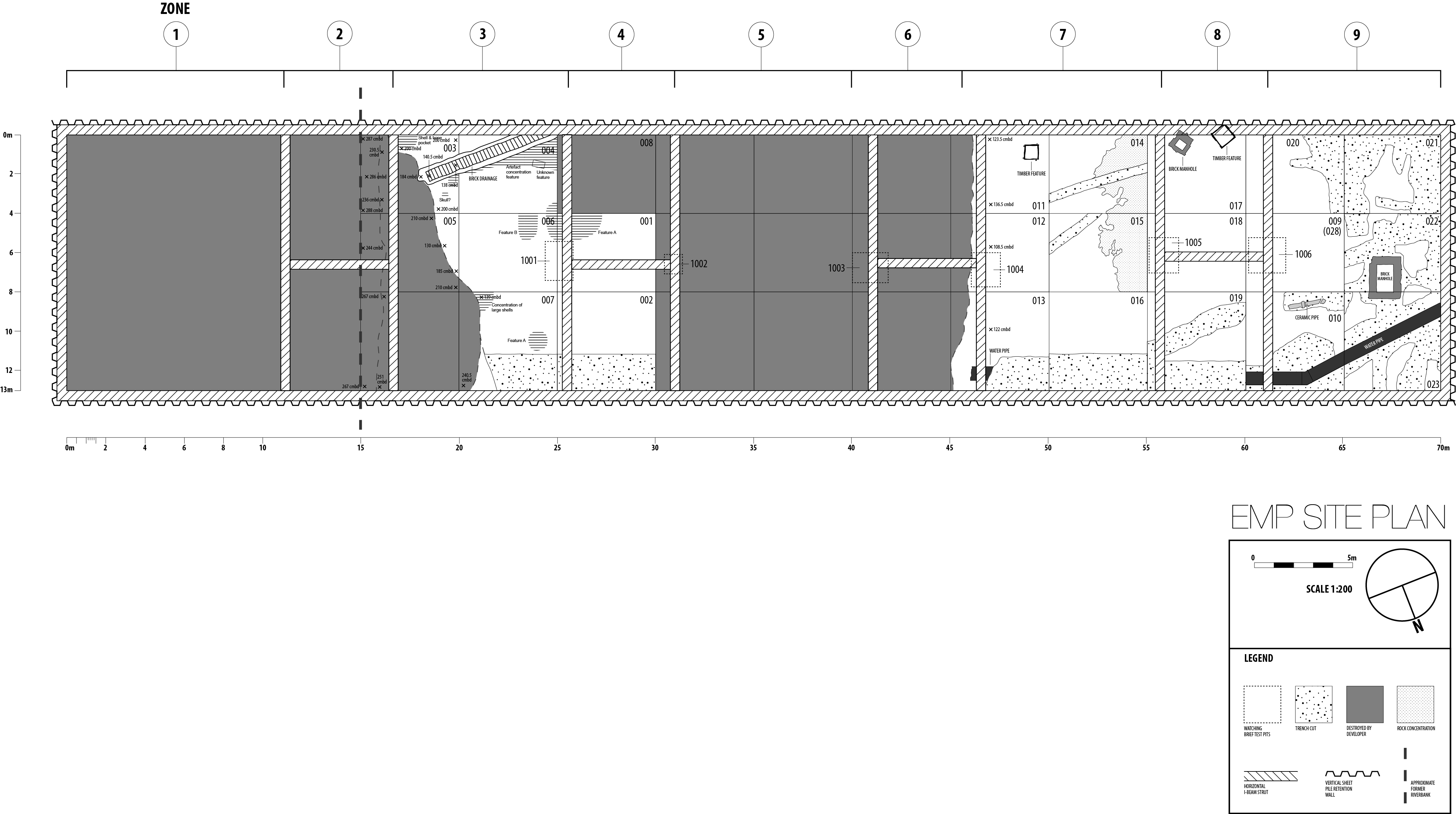

By area, the adjacent units of EMP 001 to EMP 007 form at least 17% of the main excavation area (refer to Figure 16). Except for EMP 002 and EMP 007, which are 5-metre grids, the other units are 5 metres by 4 metres. The archaeological integrity of most of the units was not optimal at the time of excavation. A modern underground pipe bisected at least 40% of EMP 002 and EMP 007, while 70% of EMP 003, 90% of EMP 005, and 20% of EMP 007 were destroyed by construction work. Unit 1001 is a much smaller unit that was excavated before contractors installed a steel support column that bordered EMP 001 and EMP 006. Due to time constraints, the artefacts from this particular unit remain unprocessed. These factors must be considered when comparisons between the units are drawn. Despite the compromising circumstances, well-preserved deposits and features are still considerable, especially in EMP 001, EMP 004, and EMP 006.

Chronologically speaking, only a small percentage (<1%) of the artefacts are attributed to the colonial period as systematic excavations only occurred at the stratigraphic transition between the colonial layer and the underlying pre-modern layer. Typical colonial artefacts such as European stoneware, white earthenwares, and CBM (Ceramic Building Material) are few to none. As such, the data in this report is representative of the pre-modern period only.

3.1. Artefact distribution and variety

In summary (Figure 18), ceramic artefacts form the bulk of the assemblage with stoneware types forming the largest group of ceramics (34% by mass), followed not far by earthenware (28%) and then porcelain (<1%). In comparison to the total ceramic yield between Temasek sites, the high proportion of earthenware at EMP is notable. While porcelain by contrast appears unremarkable, these important artefacts are still found in every excavation unit (Figure 19). Its small mass considers that celadons (and certain white-glazed vessels) are after all not considered porcelains. Researchers with a different approach may combine these figures. Until more detailed analysis tells us otherwise, the style of the porcelain provides us with a 14th to 17th-century pre-modern time frame (Figure 20).

Unusually high at the same time, is the proportion of non-ceramic artefacts (37.4%). More than half of the non-ceramic artefacts (31.5%) are made up of geological artefacts. The stone objects are incidentally the highest typological contributor. Contextually speaking, a majority of the stone artefacts are part of a non-portable archaeological feature (this will be explained further in the next section) and had their recovery not been selective, this figure would be much higher. Other non-ceramic artefacts that were often encountered are metal (3.3%) and faunal material (2.5%). Subsequent to "geological" artefacts, "earthenware tempered" is the second highest contributor (27.7%), followed by "stoneware others" (22.9%), "stoneware greenware" (6.2%), and "stoneware XKP" (3.4%).

As a dominant variety of material culture, the unusually high proportion of tempered earthenware distinguishes EMP from other Temasek sites. It is not uncommon for the weight of stoneware from other riverbank sites to be more than twice that of earthenware (Goh and Miksic 2021, 2020; Miksic and Goh 2003; Lim 2019, 2017). Furthermore, the breakdown of stoneware from these site reports excludes celadons and white-glazed stoneware, which are classified as porcelains. The higher volume of earthenware at EMP may have implications for site function and activities. Many of the EMP earthenware are wide-mouth cooking pots (Figure 21) and globular storage vessels, usually accompanied by a modest amount of fine paste vessels (<1%). Some of the more unique "earthenware tempered" decorations feature striking similarities with Johor Lama specimens (Solheim and Green 1966; Gibson-Hill 1955).

Recent studies have also shown that a significant proportion of the "earthenware tempered" objects found in Singapore are not locally made and further analysis could potentially reveal more about ancient Singapore’s maritime links (Kao 2021). Recovered at EMP are the fragments of possible oven moulds (Figure 22) used for producing staple sago-based food items such as sagu lempeng. According to Ellen and Latinis (Ellen and Latinis 2012; Latinis 2004), such implements are unique to East Indonesia, particularly Maluku. Although further analysis of the assemblage is required to determine whether these artefacts are random shipboard utensils which happened to be found on land, or part indeed of the local culture and economy, their association with food production at EMP is apparent. Researchers also believe that their distribution may be linked to the trade in spices such as nutmeg and cloves (Ibid).

In addition, the presence of charcoal, shells, and animal bones (Figure 23) in midden features strongly suggests that food preparation and consumption was widespread at the site. This is not only confirmed by the presence of what appears to be the remains of earthenware stoves (Figure 24), but also numerous stone implements that are shaped from a variety of sedimentary and igneous rocks for grinding, pounding and whetstone sharpening (Figure 25). Rare at the same time are the carbonised remains of betel nuts (Areca catechu) that were found near or within the midden features. The absence of their tough protective outer layer suggests that the seeds were not naturally occurring but were de-husked for consumption (Figure 26). Their presence also suggests that large amounts of organic items were likely present but have not survived.

Furthering our understanding of the site is the large quantity of goods that were transported between ship and shore to be traded or used and disposed of. These range from Cizhou wares to storage jars and bowls from Guangdong and Fujian province (Figure 27) to exquisite Jingdezhen blue-and-white, Qingbai, and Dehua porcelains, as well as regular and higher-grade Longquan celadons (Figure 28) from Zhejiang. In terms of more personal items, hundreds of Chinese coins (Figure 29), including high-value currency and objects such as a gold coin (Figure 30) and gold wire artefacts, were recovered (Lim 2015). However, it is unfortunate that these artefacts are not in the collection of the Archaeology Unit at ISEAS and little information about them is available.

Other rare and intimate finds include fragmentary palm-size Qingbai ceramic figurines, the significance of which at EMP remains a subject of further enquiry (Heng 2020), as well as jewellery beads and bangles made from stone and glass (Figure 31). Other fragile objects made from glass, although uncommon, are scattered across the sampled units.

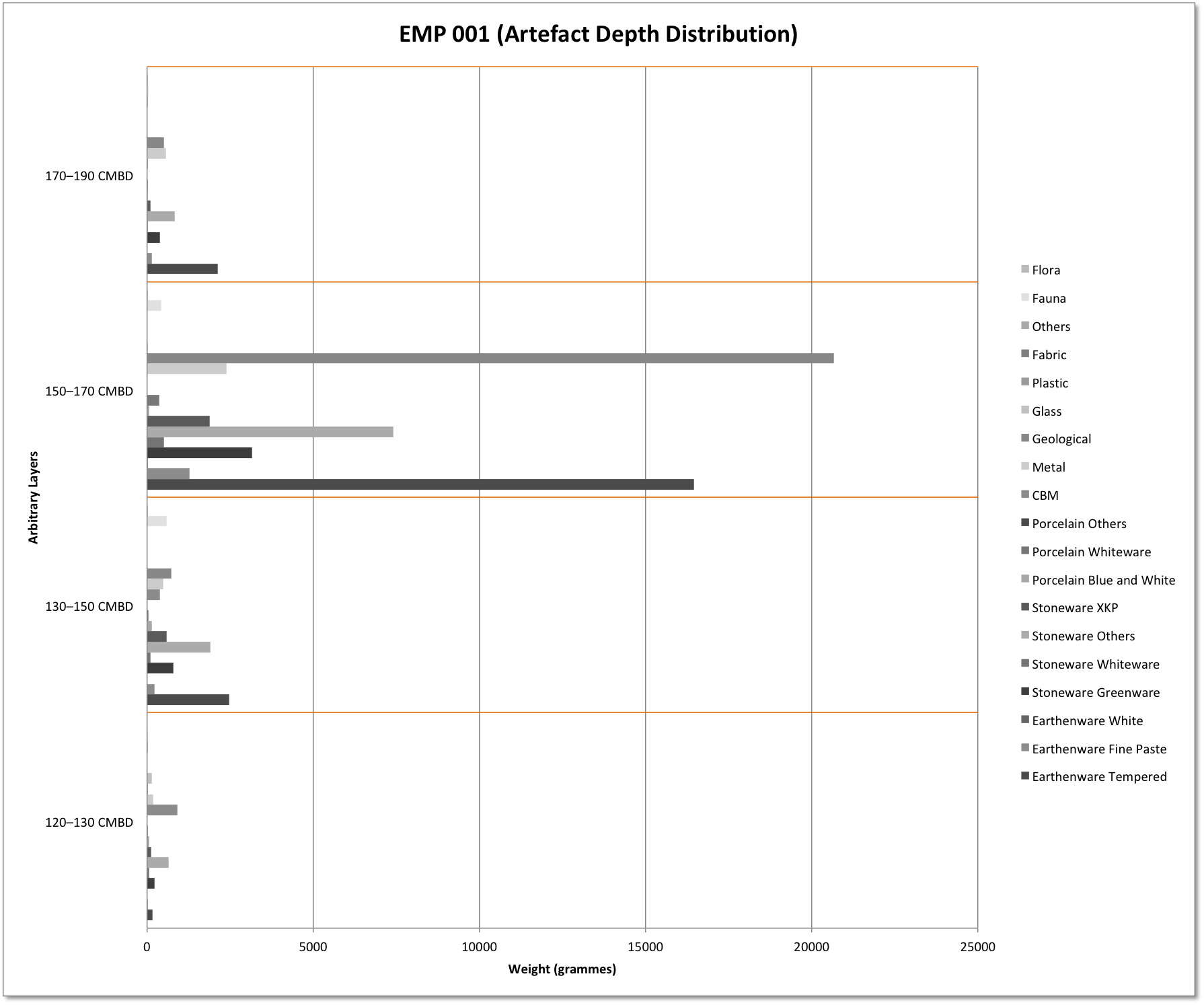

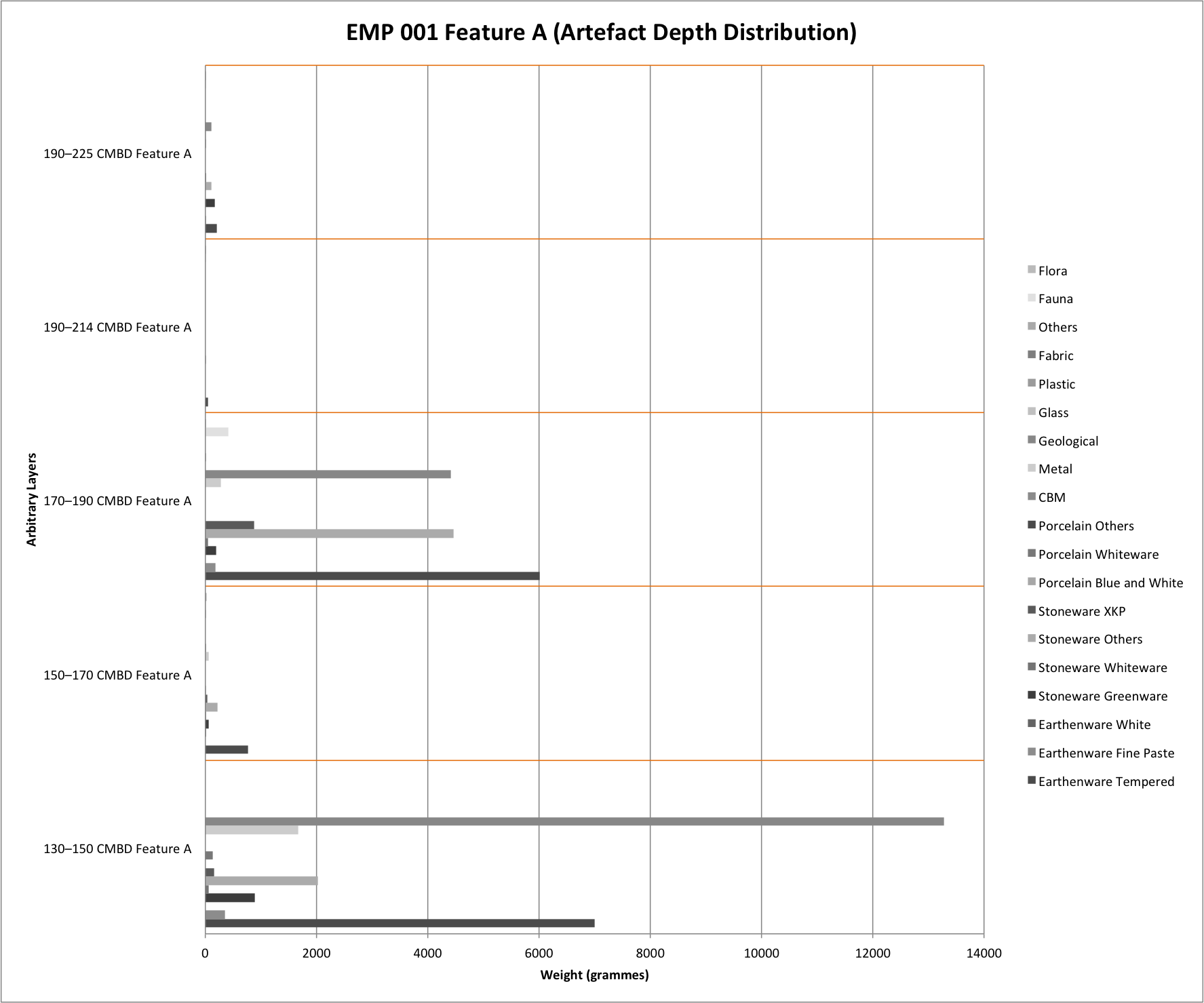

Interestingly, the artefact proportion between the units and the arbitrary layers does not differ significantly (Figure 32). This confirms the integrity of the provenance, which not only provides researchers with a wider and more robust range of sampling, but also the possibility to examine and determine the extent of specific activities and the more minute differences in site usage. Furthermore, based on the vertical artefact distribution, it is apparent that the 150 CMBD to 170 CMBD layers—featuring a spike in artefacts—reflect the peak in site occupation. Although it is yet unclear how long this period lasted, the overlying 130 CMBD to 150 CMBD layers appear to suggest that even with decline—presumably in trade and activity—people’s preference in material culture, namely pottery, did not change significantly over time. However, more research is needed to nuance any subtleties. Ultimately, the preservation of each layer enables researchers to examine various demographic changes, if any, and material consumption throughout time and space.

3.2. Archaeological Features

Distinct concentrations of artefacts were documented in EMP 001, EMP 003, EMP 004, EMP 006, and EMP 007 (Refer back to Figure 16). Of notable interest is the steep rise and fall of artefacts in Feature A of EMP 001 (Figure 33) that seems to indicate that the midden was either used intermittently or perhaps organic matter that was present has since decomposed. This may also be a by-product of a site formation process that is undetermined at this moment. This feature intrudes into the neighbouring units of EMP 004 and EMP 006. Similar features, albeit smaller in size and yet to be examined in detail, are also present in EMP 006 and EMP 007. Large shells were concentrated in the latter.

Towards the south of the sampled units, a very pronounced colonial drainpipe feature extends across EMP 003 and EMP 004 and beyond the main excavation area towards the ACM building. Partially disturbed before its discovery is a midden containing a significant amount of shell and bone and other inorganic material that was situated along the south profile of EMP 003. Although the excavated area of EMP 003 is one of the smallest, this feature, which extends beyond the unit under the modern roadway, contains the highest amount of faunal artefacts consisting of coral, shells, and animal bones. Underlying the colonial drainpipe feature and spanning the length of EMP 004 is a large concentration of 14th-century artefacts (Figure 34). Its full potential remains undocumented because the neighbouring unit (EMP 008) was destroyed by construction work. It is the richness of this midden, including the rest of EMP 004, that yielded the most artefacts by mass (34%). The volume of earthenware and stoneware in this unit is exceptional. At least 40% of all the earthenware (tempered) and stoneware (combined) recovered from all the sampled units is found in EMP 004. The artefacts from this unit are also found in considerable depth of up to 240 CMBD. From here, we may hypothetically assume that these artefacts are representative of the site’s earliest occupation.

Of notable interest is the contrast between the gradual accumulation of material culture in the earlier period (170 CMBD to 240 CMBD) and the abrupt decline (130 CMBD to 150 CMBD) presumably after the peak in trade and activities (refer to EMP 004 chart in Figure 32). More analysis is needed to determine if this anomaly is reflective of a mass exodus from Temasek at the end of its reign or simply an effect of past and recent site formation processes. Based on the similar artefact distribution pattern reflected in the neighbouring units (including the midden features), the former scenario is highly plausible.